The Zeila, Somaliland, customs station.

Beside the customs station at the tiny port in the hell-hot and dusty town of Zeila, Somaliland, two men load a large truck with crates upon crates of Tabasco sauce. Soon the Tabasco truck will trundle along the shin-deep ruts made by previous caravans of semis on the sole and makeshift road out of town, until it reaches the pit-stop in Asha Addo, where it will idle alongside dozens of other freighters funneling goods and wealth into the heart of the country. It’s a scene of commerce that might have seemed impossible just a couple of years ago, when international shippers forsook Somali ports for fear of rocket-wielding pirates.

A Zeilai import truck.

Naturally, Zeilai residents deny that locals had anything to do with the stealing of civilian ships’ booty. They will admit, however (as numerous antipiracy NGO posters in the cafes around town attest), that no matter their participation, trade ebbed and the port languished in recent years. Now, though, as the story goes, the era of piracy in Somali waters is over—although Somali pirates have struck at ships farther afield, it’s been well over a year since a hijacking in the immediate shipping lanes off the coast. The decline of the Somali pirates at the hands of an international maritime coalition; development of strong antipiracy sentiments in coastal Somali communities; and creation of a 600-man, 12-base Somaliland coast guard (one member of which I can see sleeping on a charpoy bed alongside some local fishermen down by the docks) have all received bullish coverage. Yet while the world processed the story of what happened to Somali piracy, I wondered what happens to all those hundreds of actual pirates who got scooped up in the maritime solution.

The interior cell block of the Hargeisa prison.

As it turns out, quite a few of them are making their way—in custody—to Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland, although not all of them were captured in the region. Somali pirates have a surprising range for folks operating in fishing dhows with outboard motors, and as a result they’ve been snapped up in over a dozen countries across the Indian Ocean. But few of those countries had the facilities—much less the inclination—to deal with the legal headaches related to mass influxes of foreign pirates, leading to a robust rhetoric advocating the return of Somali pirates to a Somali state for justice. It was mutually agreed that, ever eager to prove its ability, morality, and global team spirit, Somaliland would be a good repository for all Somali-pirate prisoners, no matter their provenance. The only problem was that such a relocation was both dangerous and really bad PR, given that the major pirate prison in the port of Berbera was a circa 19th–century cesspool and—Ministry of Justice officials readily admit—prone to prison breaks.

So the best solution to everyone’s problems, naturally, was to funnel in a couple million dollars in UN funds in 2010 to build an internationally acceptable, state-of-the-art prison in Hargeisa to handle pirates and other high-profile criminals like members of the al Shabaab/al Qaeda terror affiliate.

“It’s like the Ambassador Hotel,” ribs Mohamed “Wali” Isa, an official at Somaliland’s Ministry of Justice who deals with pirate-prisoner transfers. He’s referring to a swanky Hargeisa hotel frequented by the UN crowd, and as he makes his joke he shows me pictures of the whitewashed, multiwalled prison during its construction.

A window in a Hargeisa prison cell.

But it’s not entirely a joke—at least when compared with the Berbera prison. The new Hargeisa prison has around 200 staffers with international training in modern prison etiquette, and the prisoners get leisure time and phone access, soccer programs, medical facilities, and, most importantly, an active focus on retraining and rehabilitating pirates for re-release into the world. A number of pirates caught in Somaliland (although, officials stridently claim, not Somalilanders themselves) are now located in the prison, but more importantly it seems to be succeeding in its goal to become a hub for international cooperation on the piracy issue. Wali gestures to a folder in his cabinet labeled “Seychelles,” detailing two group transfers from that nation to Somaliland over the past couple of years. A third group was expected at the start of the year, but construction of the new prison meant to house them is on hold.

Taking in the prisoners everyone else sees as a headache (and reportedly treating them relatively well) has been good political business for Somaliland. Wali stresses that a significant part of the prominence and care in prison reform and piracy law is the recognition of Somaliland’s responsibilities for the security of its waters and the incentive to maintain open trade routes. However, he admits that the implicit political message sent by Seychelles’ cooperation with the Somaliland government is a nice perk too. He characterizes the deal with Seychelles as a form of de facto recognition for the nation’s independence—all the more important now that international attention is being drawn toward a new government in Mogadishu to the south. Cooperation on piracy has also led to the first official meetings between the presidents of Somaliland and Somalia in over a decade, and contracts between the UN and Somaliland treating the latter as an autonomous entity (although not as a sovereign nation state). Given that most mainstream political rhetoric and strategy in the nation—the answer to every ailment—is “achieve recognition,” there’s been a strong incentive to make real and full efforts at what might otherwise be empty goals of quality, training, and rehabilitation.

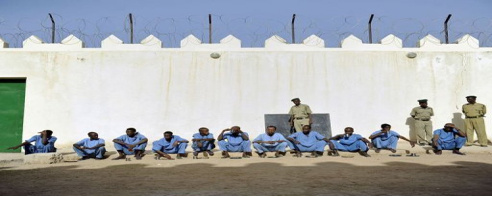

Prisoners at Hargeisa prison.

The skills training and educational programs Wali mentions are probably something most Somalilanders would clamor to get access to. Aside from classes in English, computer training, and math, there are practical courses in brick making, welding, painting, and carpentry—all skills high in demand in a country with almost no vocational training. In fact, the absence of native skill in such practical trades has led, despite massive local unemployment, to recruitment of Ethiopian and Yemeni laborers to fill jobs in cities like Hargeisa. So one would think this was the ultimate win-win: score international points, reportedly do a good job at something other governments would botch, gain a new Somali workforce, and effectively integrate pirates (and their new salaries) into local communities (and economies). The only problem is that, despite all the time and effort, Wali says the government has no earthly intention of integrating these pirates here, not into Somalilandsociety.

A truck stop outside Zeila.

This resistance to the repatriation of the Hargeisa pirates seems to stem from the overarching local rhetoric that none (or only one or two) of the Somali pirates are actually Somalilanders. Just as the legitimate claim that there were no pirate bases or attacks directly on Somaliland’s coast over the years helped to bolster the nation’s sense of security, there’s significant national and rhetorical value in the visible disassociation of Somaliland from any connection to piracy, save antipirate justice and security.

Although Wali will reluctantly admit that they don’t really completely know the true identity of all the prisoners, he insists that all of the pirates currently in the Hargeisa prison are members of the Hawiye clan from warn-torn southern Somalia. When the new international darling government in Mogadishu gets on its feet and builds a prison up to international standards, he says, they will transfer all of the prisoners there. And even if Mogadishu never completes its prison, if the new government fails and international cooperation once again re-centers primarily upon Somaliland and neighboring Puntland in the north, Wali maintains that they will deport the prisoners to the south after their terms are complete.

The inevitability of the transfer south makes the whole venture feel a little hollow. To Wali, the value of the rehabilitation seems to lie in the image of competence, international cooperation, and compliance it projects, not to mention, he says, that it keeps the prisoners’ active and limits their time to plan escapes (Shawshank adventures appear to have been quite common in the older prisons). But the part of the plan that deals with the actual value of that training beyond the cell walls, the integration of pirates as rehabilitated citizens, and their potential to become valuable members of a local economy, has become a buck to be passed along the line to another government. At best, if the government in Mogadishu stabilizes, then Somaliland lends its southern neighbor a hale and healthy influx of workers while steadily taking on the task of rehabilitating pirates from a grateful and overburdened Indian Ocean community. At the worst, they reintroduce ex-pirates to war and chaos, it all goes to pot, and they falter, recidivate, or worse. But for now the best we can say is we know where the pirates are washing up and what they’re up to now.

More Somaliland:

Somaliland Is a Real Country, According to Somaliland